Finding belonging in Cuban baseball

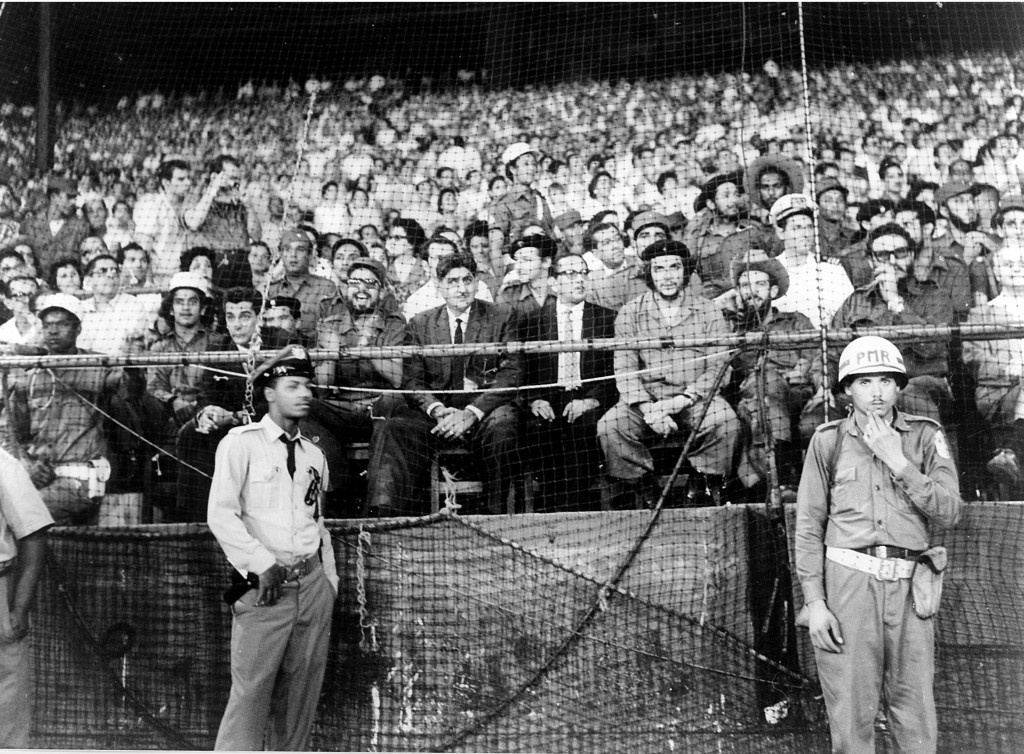

What a posse taking in a Havana ballgame: (Che’ Guevera (1928-1967) with beret); to his left is Raul Castro, to Che’s right is baseball player and revolutionary hero Camilo Cienfuegos (1932-1959), Fidel Castro is to the right of Cienfuegos. I bought this picture a few years ago at an antique store in Little Havana outside of Miami.

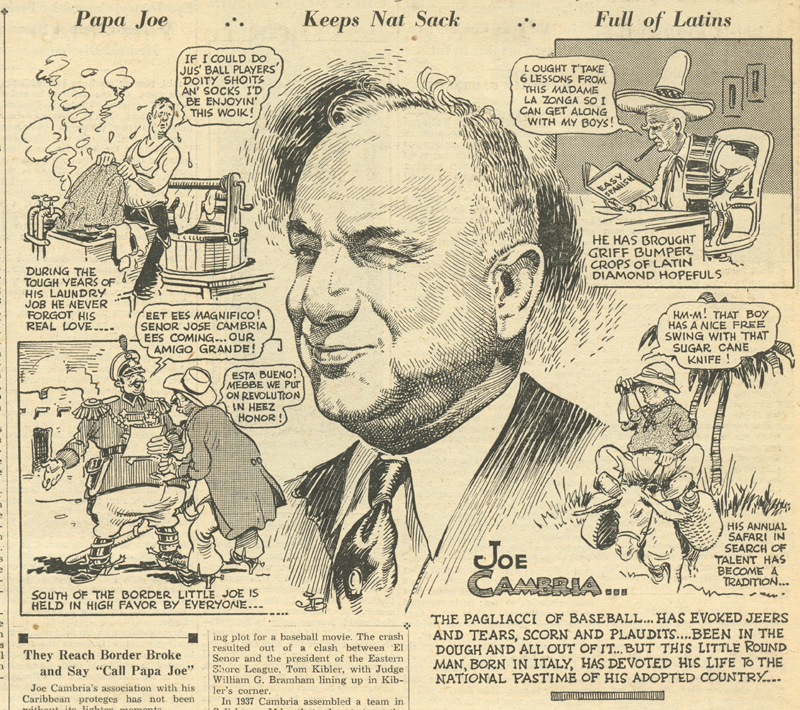

Joe Cambria charmed an island that is used to bewitching moments.

Once the owner of the largest laundry in Maryland, Cambria scouted Cuba for the Washington Senators/Minnesota Twins from 1934 to 1962. He is known for tooling around pre-Castro Cuba with a loaded cigar and his chauffer, a retired highway patrolman who drove a big fat Lincoln.

Cambria was in the business of importing dreams. He held court with a female correspondent from Minnesota who followed him in search of something that reminded her of home.

Cambria lived at the American Club in Havana. He leased a restaurant and tavern, the Bar Triple A, over the right field fence of the Estadio Lationoamericano ballpark (opened October, 1946) in downtown Havana. There was always music as there always is in Cuba. He loved the beat of the rumba which Congolese slaves had taken to Cuba so long ago.

Cambria connected with the resilient spirit of the Cuban people, who gave him the nickname “Papacito” (“Papa”) Joe. They even named a “Papacito Joe” cigar after Cambria. His face was round and jolly, just like something the natives would see on welcoming Yankee currency.

The effervescent Cambria signed more than 400 Cuban ballplayers in 25 years.

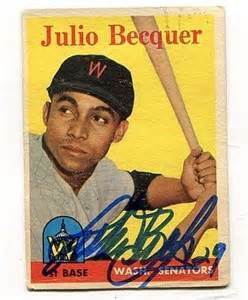

He scouted Fidel Castro. His Cuban major league alumni includes Camilo Pascual, Tony Oliva, Preston Gomez, Pedro Ramos, Zolio Versalles, Julio Becquer, Sandy Consuegra and Willy Miranda. Cambria also discovered the first Venezuelan major leaguer, Alex Carrasquel, whom he saw pitching in Havana in 1938. Cambria signed Venezuelan outfielder Vic Davallillo and his older brother Yo-Yo, as well as American players Early Wynn, Mickey Vernon and Eddie Yost.

Papa Joe unearthed Joe Krakauskas, surely professional baseball’s only Canadian-Lithuanian. A southpaw, Krakaukas topped out with an 11-17 record for the 1939 Senators, with 110 Ks (and 114 walks) in 217 innings. He plucked Allen “Bullet Bob” Benson from the House of David barnstorming team and Benson made his 1934 major league debut with the Senators. His career lasted two games.

Papa Joe was dispatched to Cuba because of the tightwad mentality of the Griffith family who owned the Senators and the Twins. When Camilo Pascual arrived in the major leagues with the 1954 Senators he discovered his pitching coach was ex-White Sox pitcher Joe Haynes—the brother-in-law of future senator owner Calvin Griffith.

That’s cutting corners.

During a 1991 interview in his Florida condo Griffith said Cambria scouted Fidel Castro, a somewhat effective left handed sidearm pitcher, who at the age of 18 was proclaimed as “Cuba’s outstanding athlete.” Castro once swam more than seven miles in the ocean to escape an assassination attempt. He may even still be alive today, at the age of 88.

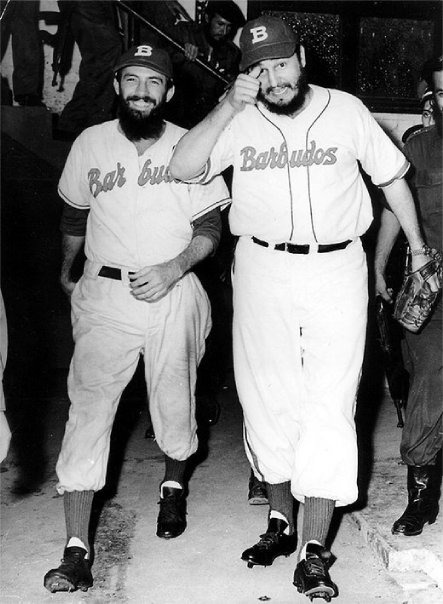

Fidel Castro (right) and Camilo Cienfuegos in 1959 when they played for Barbudos (“The Bearded Ones.”) A spirited leader of the revolution, Cienfuegos became canonized in Cuban culture in 1959 after his Cessna 310 airplane disappeared over the ocean. He died at the age of 27.

Cambria first saw Castro pitch when Castro was a teenager in the center of Havana and he followed his career until Castro enrolled at the the University of Havana, where politics took precedent over sports. “Joe got in good with Castro,” said Griffith, who kept an autographed baseball from Castro in a trophy case next to an autographed baseball from fellow chairman Frank Sinatra. “Papa Joe told him, ‘Your fastball isn’t fast enough.’ But he still pitched in college. A sidearmer? I don’t know what the hell he was. But Joe Cambria and Fidel Castro got to be buddies. About the only Cuban he missed was Minnie Minoso.”

“Baseball was in Joe’s blood. He lived on olive oil and garlic. Every time you cooked, you had to have olive oil and garlic for him. He was a one-man show. You don’t get to be called ‘Papa Joe’ unless you are a good citizen. He did everything in the world for the Cubans. He literally was their Papa. He gave them things they never had before. Whatever he had in his pocket. Money, clothes.”

Who was Papa Joe?

* * * *

Joseph Carl Cambria was born in Messina, Italy on The Fifth of July, 1890.

His family came to America when he was eight months old and he was reared in Boston. Cambria was an outfielder for Newport in the Rhode Island State League and barnstormed with St. Louis Browns pitcher Urban Shocker. Cambria retired after breaking a leg in 1916.

After serving in the military in World War I, Cambria relocated to Baltimore and opened the Bugle Laundry. By 1928 it was the largest laundry in Maryland. The laundry supplied jackets and towels to Baltimore business houses.

The Bugle Laundry also sponsored a semipro team and played under temporary lights on a diamond Cambria named “Bugle Field.” Calvin Griffith was a reserve member of the team. His uncle Clark G. Griffith owned the Washington Senators. When Clark died in 1955, Calvin inherited the Senators. He moved the team to Minneapolis in 1960.

Clark Griffith had paid close attention to Cuban pitcher Dolf Luque, a major influence on future Senator and Twin Camilo Pascual. Luque helped Pascual master his wicked curveball. At age 42, Luque joined the New York Giants in 1932 and helped them to the National League Pennant. Luque pitched four scoreless innings in the 1932 World Series.

After that performance, Clark Griffith got the idea to dispatch Cambria to Cuba.

“By that time Joe ran several ball clubs himself,” Calvin Griffith said. “Hagerstown (Blue Ridge). Albany (International League). Salisbury

(Eastern Shore), Greenville (Sally), Youngstown (Middle Atlantic, where Cambria also was a manager).” In 1933 Cambria also owned the Baltimore Black Sox of the fledgling Negro National League. He took players off salaries and operated on a percentage basis to remain fiscally solvent during the Depression.

“He has been called a sharpshooter and fly-by-night operator,” Frank O’Neil wrote in the Jan. 18, 1945 edition of The Sporting News. “He has been indicted as a man who could squirm out of an eel trap, and discredited as a hazadorus risk to any league in which he might obtain a franchise.”

But by mining Cuban talent, Cambria was setting the stage for the integration of baseball in America. Until Cambria’s arrival, the only

Cubans in the major leagues were Adolfo Luque and Miguel Gonzalez.

People don’t realize the Cuban prelude to integration.

* *

Jackie Robinson broke through major league baseball’s color line in 1947. But, between 1911 and 1947, about a dozen guys in the major leagues had played in the Negro Leagues. They were Hispanic. They were black enough to perform in the Negro Leagues and white enough to play in the Major Leagues.

John “Little Napoleon” McGraw would do anything to win. He was always looking for the edge when he managed the New York Giants between 1901-1932. [Bill Veeck’s midget at bat was inspired by a little person named Eddie Morrow that McGraw kept in the club house as a “good luck charm.”] McGraw knew there were players of color in Cuba. He had no racial agenda. He just wanted to win.

The 1933 Albany Senators were one of the first teams Joe Cambria stocked with Cubans. A setting for the moody baseball novel “Ironweed,” Albany had the smallest population of any city in the International League. It was a no-win proposition, but Cambria used money from his Baltimore laundry to finance the operation.

Cambria took over the International League franchise from the Chicago Cubs. In 1933 the Cubs optioned Stan Hack to Albany to play third base. Hack was a colorful Senator. “Something about playing with the men of Cambria made him do strange things, especially like climbing the light tower in left field,” Joe Buchiccio wrote in the Nov. 1968 edition of “The Evangelist.” Despite being Cambria-ized, Hack still made the league’s all-star team that year.

Cambria thought outside the box.

His 1934 Senators featured outfielder Fred Sington, a former Alabama football star who led the league in RBIs (147) as well as Cuban imports who could neither read or write in English. Cambria gave them identification tags to wear around their neck in the event they became lost. The team’s future Cuban major leaguers included MIke Guerrera, Tommy DeLa Cruz, Bobby Estallela and Reggie Otero, who went on to coach for the Cincinnati Reds.

In 1935 Cambria signed Alabama Pitts to a contract, which forever made Papa Joe part of Albany sports lore. Pitts was a 25-year-old ex-convict with a honest-to-goodness baseball reputation. He had just been released from Sing Sing Prison in Ossing, N.Y., where he was doing time for armed robbery. Cambria instructed his general manager Johnny Evers to pay Pitts $200 a month. The acquisition was overruled in the courts and also by Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. But Cambria and the Senators won out.

In June, 1935 more than 7,000 fans came to see Pitts baseball debut.

The field was flooded with water from an all-night rain. Cambria burned gasoline on the field to get it into playing condition. Pitts went

2-for-5, but finished the year hitting .233 in 116 at bats and striking out 24 times. He missed many games due to injuries. According to the Aug. 29, 1935 issue of the Sporting News, Pitts went down with blood poisoning which resulted when he “spiked himself and paid little attention….until his foot swelled.”

Pitts was done. He was released at the beginning of the 1936 season. Pitts died in 1941 from knife wounds incurred in a roadhouse fight after he had played in a game with the semi pro Valdese (North Carolina) mill team.

Cambria already had enough.

The 1935 Senators were dreadful, finishing in last place with a 49-104 record. They weren’t much better in 1936, finishing last again with a 56-98 record, despite having the league’s leading hitter in Smead Jolley (.373), who had flamed out with the Chicago White Sox. After the 1936 season Cambria sold the Senators to the New York Giants for $75,000. The Giants moved the club to Jersey City, where they finished last again with a 50-100 mark.

* *

Helen loved to visit Joe at the American Club. She was a young feature writer for United Press International and had met Papa Joe down the road at the Tropicana nightclub. The American Club was a safe haven. The hearty food reminded her of the restaurant her parents ran back home in Minneapolis. She was supposed to work in that place, too. She grew up behind the counter and quickly came to understand the regiment of the working class. She heard the complaints. She saw the creases that ran across the faces of old men like threads in a quilt.

And she hated snow.

Joe took great delight in the American Club’s spaghetti and the spicy nature of the Cuban seasoning. He would talk about the discovery of another mediocre Cuban ballplayer that he could fly under the radar back to Washington, D.C. Helen would talk about the latest Saturday Evening Post that had landed at the club. There were stories about Wyoming and poems about broken music boxes.

Helen and Joe adored the artwork of Cuban Andres Garcia Benitez that adorned the covers of Bohemia and Carteles magazines. Garcia Benitez preceded the popular Vargas in the pages of Playboy magazine. Garcia Benitez also produced images of Cuban team pinup girls wearing colorful team jerseys.

Helen had a calming effect on Joe’s restless nature. Joe never married and he had no children. “My kids are on the fields of Cuba and Venezuela,” he would say. Joe was no longer a young man when Helen met him in 1944. They were an odd couple who were friends more than companions. Helen was tall and lithe and her Scandanivan complexion did not like the tropical sun. Joe was short and squat and he loved Panama hats that on occasion shaded his blue eyes. Their direct nature was their connective thread, their mojo that made them friends. Helen was straight-ahead in a practical Midwestern sense. Joe confronted everyone with his Catholic-Italian brotherhood. He would wrap his arm around the shoulder of a young ballplayer and sell him a dream. He did this thousands of times across the entire island of Cuba. Helen wondered what it was that drew him to the game of baseball like a match to a cigar.

Sometimes he wondered where the time went.

* * *

On Jan. 7, 1945 Papa Joe was presented with a gold watch by Cuban ballplayers who had reached the major leagues between games of a winter league double header at La Tropical Stadium in Havana. Cuban baseball writers gave Cambria a bronze plaque. More than 15,000 fans paid tribute to Cambria.

Tomas de la Cruz of the Cincinnati Reds—who earlier in the week had pitched a no-hitter for Almendares—made the player’s presentation with Papa Joe looking on. Speeches were given by Rogelio Valdes Jorge, president of Cuba’s professional league and Merito Acosta, who was a star for Louisville in the American Association. Helen was in the stands and began to understand the bridges Joe was building.

Riding high with the Cuban people, in 1946 Cambria founded the Havana Cubans of the Florida International League. It was the same year the Brooklyn Dodgers signed Jackie Robinson and moved spring training to Havana to escape the segregation of the United States.

The Cubans played their maiden season at the La Tropical Stadium. Bobby Maduro bought the team in 1954, renamed it the Sugar Kings and relocated it to El Gran Estadio del Cerro (a.k.a. Gran Stadium) in Havana. The Cubans delivered future major leaguers like former Cubs manager Preston Gomez and pitcher Camilo Pascual.

Pascual became Cambria’s best friend. Cambria was best man at Pascual’s 1958 wedding in Havana. Cambria discovered Pascual when he was a 16-year-old third baseman on Club Ferroviario (named after a Cuban railroad) in Havana. “He watched every game from a distance,” Pascual told me over a 2002 breakfast at the Versailles Restaurant in Little Havana, outside of downtown Miami. “He would sit in the stands, down the third base line. He wore white shirts with Panama hats. He told me I was going to be a pitcher. He knew.”

He saw the national pride of the Cuban athlete.

Clark Griffith was a minority Havana Cubans owner which created the pipeline to the Senators. Conrado Marrero and Sandy Conseuegra all played for the Cubans between 1946 and 1950 when they won four consecutive Florida International League titles. The Class C league also had teams in Miami, Miami Beach, Tampa, West Palm Beach and rural Key West.

During the regular season Fidel Castro attended Sugar Kings games at Gran Stadium. Not long after assuming power he pledged to underwrite the Sugar Kings debts. During the Cuban Winter Leagues, Castro followed the Alamendares Club of Havana, whose heritage dated back to 1879. The Almendares mascot was a scorpion and the team motto was “He who defeats Almendares dies.”

Hall of Famer Monte Irvin played for Alemandares between 1947 and 1949. He batted against Castro, who pitched batting practice. “He would work out with us,” Irvin once told me. “He had a fair amount of speed, but his control wasn’t what it should have been. Marrero once said, ‘If we had known he wanted to become a dictator, we would have made an umpire out of him.”

* * * *

In the late 1940s Helen received an assignment from U.P.I. to write about the cigar factories in Pinar Del Rio. The fertile tobacco growing region was about two hours from Havana. She had no way to get to Pinar Del Rio. She asked Joe to accompany her. Joe liked cigars and Benny More’. The Cuban songwriter got his start in these factories, composing songs like “Sete Cayo’ El Tobacco.”

And Joe had a driver.

“There was a boy from Pennsylvania named Alex Kvasnak,” the driver told Helen as they waited for Joe to emerge from the American Club. “Joe called him ‘Squash-Neck.’ Not a bad hitter. Squash Neck had quite a reputation around his home town and word got out to the Red Sox that Joe was sniffing around. The kid’s father was a barber. He couldn’t make up his mind between Joe and the Senators and the Red Sox.” “Splitting hairs,” Helen said, adjusting her wide brimmed hat.

“So you know what Joe does?,” the driver said while looking at Helen in the rear view mirror. “He had a brand new barber’s chair delivered to his father’s shop. And Squash Neck signed with the Senators.”

Helen looked out at the American Club and wondered. Was Joe an operator? Or did he explore every possibility in life? Did his open spirit contrast her shadowed nature?

Joe rolled out of the American Club like a red carpet in Hollywood. He had the whole bit going on: Panama hat, light white shirt with a pocketful of cigars and a satchel with a bottle of Havana Rum sticking out from the top. He seemed excited about the day trip, but there was no way Helen could tell for sure. He was a scout. He knew about the music around the factories such as the percussive punto pinareno that was indigenous to Pinar Del Rio. Maybe he would find a baseball game along the way. This day trip was where Helen learned that Joe never liked to see the sun set.

* *

Former Washington Senator/Minnesota Twin Julio Becquer was scouted by Cambria and kept in touch with Papa Joe his entire life. “Joe always knew what we were doing,” Becquer said in a mid-1990s conversation in his Minneapolis home. “We didn’t call him on the phone or things like that, but especially when we went to Cuba he would help us with accommodations. He would always inform the major league clubs what we were doing in Cuba.”

When Cuban ballplayers arrived in the United States, Cambria would take them to Spanish restaurants. After signing Carrasquel, the first Venezulean in the big leagues, Cambria gave him dozens of rumba records to keep him from being homesick.

Becquer played for Havana in the Florida International League (1953, 54), San Diego in the Pacific Coast League (1955), the Senators (‘55, ‘57 and ‘58) and Louisville in the American Association (1956). “There were so many Cuban players in triple AAA in 1956 it was unbelievable, nearly 100,” Becquer said. “ Philadelphia had Tony Gonzales, Cookie Rojas, Ruben Amaro, Tony Taylor. And that’s only a few. You go to Cincinnati and there was Leo Cardenas, Tony Perez.

“We always had a group and we stayed together. Cubans ate together, we slept together, we played together. We got along well. I knew there was racism. In Louisville I was called everything. I never acknowledged it, but we didn’t forget. I was trying to avoid confrontation. I came to the United States to play ball. But we protected each other.

“If you had to deal with one, you had to deal with the rest of us.”

“And you cannot win. The only way you can win is if you eliminate all of us.”

Becquer met his wife Edith in 1951 in Havana. She was studying to get her Pharmacy degree from the University of Havana. They got married in 1961, the year Castro cut off Cuba and ended professional sports. “After Cuba closed off, that was it for Joe,” Becquer said. In firm tones Edith added, “Papa Joe is the reason I am in this country.”

Joe Cambria died in 1962 in a Minneapolis hospital. Cuban balll players across America shed a tear for their papa. Joe had long lost touch with Helen, who relocated to New York before the 1959 revolution. She also had raised a family.

Leave a Response