A Life Beyond Baseball

Mets pitcher R.A. Dickey and his kids in NY subway (Courtesy of R.A. Dickey)

May 29, 2012—

The honest sports memoir floats in rarefied air.

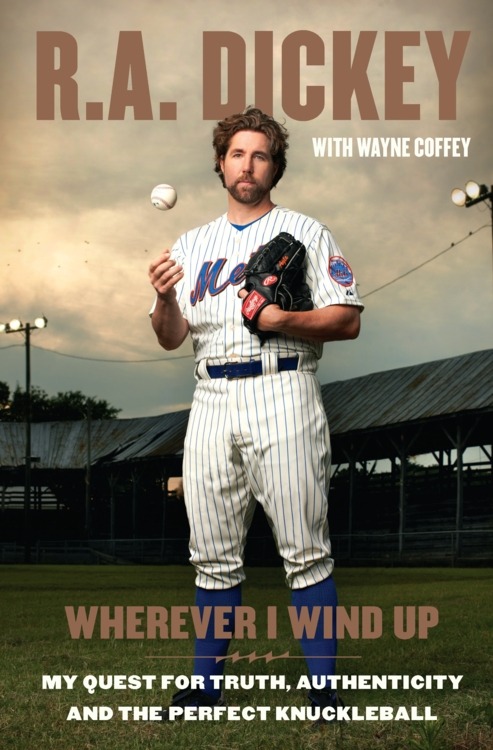

The majority of sports remembrances flutter and roll like tumbleweed into a moonstruck horizon. But New York Mets pitcher R.A. Dickey has written “Wherever I Wind Up: My Quest For Truth, Authenticity and the Perfect Knuckleball (Blue Rider Press, $26.95), one of the most soul-searching memoirs of any recent genre’.

Robert Allen “R.A.” Dickey was born in 1974 in Nashville, Tenn., where he still lives with his family in the off season.

He was sexually abused as a child. His mother was an alcoholic who baby sat her son at a Nashville honky-tonk. His parents split and several times Dickey slept along by breaking into empty Nashville houses. He considered suicide. He became a Christian.

Dickey fell in love with literature in the 7th grade.

He was already looking for an escape.

“I started journaling then, whether it was about my life or experiences I had on the baseball field or football field,” Dickey said earlier this spring in a morning phone call from the Mets clubhouse in Houston, Tx. “Teachers, coaches friends. I kept the journals. They were in neat, 80 page spiral notebooks. As I grew I would sit it down and pick it back up.”

Some memories are heavy.

Dickey began writing his memoir in 2008. He was 33 years old and pitching for the Tacoma Rainiers, the Class AAA affiliate of the Seattle Mariners.

“I had gone through a lot of counseling to get the equipment and vocabulary to talk about my experiences in a way that were relateable,” he explained in a measured cadence. “I was on an inflatable air mattress overlooking Puget Sound in Tacoma, Washington. It was a sparse, two-floor townhouse. I thought it was time. Whether it was more my own creative psyche or God’s voice, that’s for someone else to determine but I felt compelled to start writing. And I did.

“I wanted to write the hardest stuff about my story first to get it out of the way. I started and had to stop after two weeks. It was too painful. I wasn’t ready yet.”

Dickey returned to the project in 2010 and then put the pedal to the mettle.

Dickey made it through his formative years to become a start pitcher at the University of Tennessee, where his teammate was Todd Helton. Dickey majored in English literature at Tennessee, where he was named an Academic All American. Dickey was a member of the 1996 U.S. Olympic team. He was signed buy the Texas Rangers to an $810,000 contract, only to have that taken away when it was discovered he did not have a ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) in his right elbow. Without a UCL, Dickey writes that it should hurt him to run a door knob or to shake hands.

And he is a baseball pitcher.

Make no mistake, professional sports is entertainment and the entertainment business is full of smoke and mirrors. I know. I’ve covered entertainment (and sports) for 27 years at the Chicago Sun-Times.

I asked Dickey how difficult it was to be so candid.

“That is an astute question,” he answered. “I spent a lifetime trying to hide behind things. I built up mechanisms for being able to deal with things that were very unhealthy. When I met Stephen James (a Nashville therapist) he gave me the gift of living differently. And part of living differently is being honest and embracing things hard and beautiful and being able to walk forward with both. So when I decided I was going to write this book I knew I was going to write it as honest as I could write it. It was important for me to talk about myself and not other people. I obviously have the most experience with me.

“And that was the lens I wrote through.”

Dickey and his co-author Wayne Coffey of the New York Daily News made the dicey decision to write in the present tense.

Present tense has more impact, but it is a device rarely used in a memoir. “It was risky,” Dickey said. “Having appreciated all kinds of books I know most are not written that way. That’s where Wayne came in and was real helpful. It was a step of faith. It just worked and it flowed. I can’t write in the present tense as an 8-year-old boy writing like a 37-year-old man. As I grew in the book, the vocabulary would change and the sentence structure started to change. It kept the same rhythm but I didn’t have the vocabulary as an 8-year-old boy that I do now, so I wanted to make sure we stayed true to that. It was the best way to communicate to the reader. I don’t think it works for every memoir, but it certainly was the right way to write mine.”

Dickey cited a handful of teammates who are avid readers.

“Mike Nickeas (reserve catcher), Mike Baxter (outfielder), they are voracious readers,” he said. “Jason Bay is a reader. (Cleveland pitcher) Kevin Slowley is a big reader. Of course I’ve been on four big league teams: Seattle, Texas, Minnesota and New York, so that’s my sample size.”

The baseball community has reacted different to the wonderfully titled “Wherever I Wind Up” than what Dickey calls “the locker room community.”

“The locker room culture has been great,” he said. “There hasn’t been one person who questioned, ‘Why did the hell you do this?’ There is much more encouragement and even more than that, curiosity about my story—which is great for a relationship. A couple of teammates have shared similar experiences in their own lives. It was unexpected. After the Sports Illustrated story came out (April 2) and excerpts of the book were printed, I remember pulling into the parking lot at (the Mets spring training site) Port St. Luice with anxiety. ‘There’s no turning back now.’ Then throughout the day three or four people came over and asked me how I was doing and was curious about my story. It was unexpectedly incredible. Not to stereotype, but not a lot of baseball players are big readers. I was surprised.

“Now in the baseball community; writers, media, coaches there were two sides. You just didn’t talk about it because it was too personal. Or, it was coming up and saying how much they liked the book. I was very blessed in the response I got in the framework of the baseball community.”

Dickey has read the sports classics like Jim Brosnan’s “The Long Season,” fellow knuckleballer Jim Bouton’s “Ball Four” and Elliot Asinof’s “Eight Men Out.” According to Sports Illustrated, he was reading F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Beautiful and the Damned” during spring training. Dickey has been known to name his bats for literary swords, such as Ocrist the Goblin Cleaver (from The Hobbit).

Former White Sox pitcher Charlie Hough mentored Dickey on his knuckleball and turned his career around into the success Dickey is having this season.

Here is Dickey’s description of meeting Hough: “He has the leathery look of a character from an old Western, a guy who has smoked too many cigarettes and used too little sunblock. He looks as if he’d spent most of his life squinting and the rest of it in a saloon. His shoulders are sloped, his hands are weathered, his crow’s-feet all but carved into the corners of his eyes…”

That’s good stuff.

Dickey checks out books stores when he travels. “Any time I’m on the road I try to immerse myself in the city,” he said. “I try to take public transportation if I can. I’ll go to bookstores. Those are things I do regularly.” Dickey takes the subway in New York and in the off-season he lives near the acclaimed Parnassus Books in Nashville. “Its four minutes from my front door,” he said. “Its nice to see people taking that independent risk in the Internet age and Books-A-Million Age.”

During the off season Dickey, Slowey, Mets bullpen catcher Dave Racaniello climbed to Uhuru Peak, the highest point on Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest mountain in Africa. The trip was inspired by Dickey’s fascination with Errnest Hemingway’s 1936 short story “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.”

“The short story is not about a mountain necessarily,” Dickey said. “But he’s always in the shadow of the mountain. The first paragraphs in particular describe Kilimanjaro as a real mystical place. That’s always registered in my mind. I thought, ‘I’d like to do that one day.’ As I got older I thought more and more about it. I was going to have to the opportune moment and it presented itself last year. I took the steps of planning it out and I was planning it out I thought about trying to support a charity.”

The journey of the baseball men was to raise awareness for Bombay Teen Challenge, an outreach that rescues girls and young women from human trafficking and sex slavery in Mumbai and the red light districts of Kamakpaura, India.

“I met the executive director and founder of the outreach when we went to Atlanta to play the Braves,” Dickey continued. “I really connected with it. I have daughters of my own, 10 and 8 and thought of them being subjected to what these girls are subjected to. It almost felt criminal if I didn’t do something.

“That got me full bore bout the Mets being upset about it for the danger of it. They sent me a letter not saying that they would, but they could void my contract if I went and got hurt. They asked me to reconsider. I certainly understood them having that concern but I was committed to going.”

Good thing that the Mets left Dickey alone.

As of this post, he is 7-1 with a 3.06 ERA, 61 strike outs in 64 innings.

I asked Dickey what music he had on his iPod for the climb. As a lifelong resident of Nashville and someone who did serious time in Oklahoma City, I thought Dickey might have a mountain of country music.

“One would think I was into country music,” he answered. “I certainly appreciate country but I’m thankful I have an appreciation for a lot of different genres of music. On my iPod I probably have four or five country singers. I love contemporary opera. Classical music. I love ‘80s bands. About an hour into the climb the iPod froze up. It was awful. I had this pump up mix like Survivor’s ‘Eye of the Tiger’ ‘Burning Heart,’ (by Survivor) all the Rocky songs. I knew it was going to be hard and I would need motivation. I crap you not, it froze up after 45 minutes into the climb. And I had seven hours left to climb. I love contemporary opera. Classical music. I love ‘80s bands. ”

Dickey wrote about his climb for the New York Times Baseball Blog.

Dickey is also involved in the Honoring The Father ministry where he takes baseball supplies to Cuba and other Latin American countries. “I’ve been to Cuba several times,” he said. “I started going in ’97. We take everything from medicine to aspirin. Especially in rural areas they don’t even have electricity in some places. We take baseball equipment and put on baseball clinics. There’s a network of guys in baseball right now that are involved in ministry in some capacity so we round up the baseball stuff. Things I keep throughout the year, I’ll send five or six boxes down.”

Dickey said he has actually pitched for a Cuban team outside of Havana. He also competed for the U.S.A. against the great Cuban third baseman Omar Linares in the ’96 Olympics in Atlanta, Ga. Dickey said, “You’ll go into the most poverty stricken community, dirt floors, no running water. And then you will see a perfectly manicured baseball field. Not every baseball player you pull out of Cuba is going to be the next Nolan Ryan, but it has become this thing, that if they can hold on to it, may be a ticket off the island.

“Baseball is really the universal language in Cuba.”

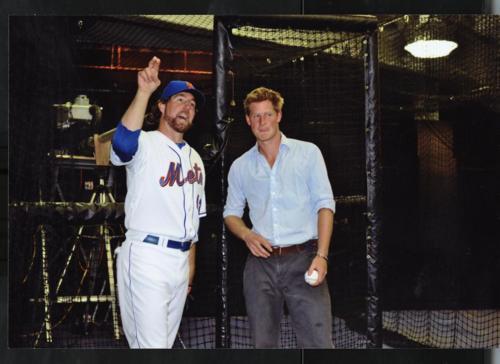

Fidel Castro knows how to pitch, but Prince Harry learns the knuckler.

Dickey is also featured in the “Knuckleball” documentary that premiered this spring at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York. The film features Dickey and just-retired knuckleballer Tim Wakefield who says in the film that Jose Canseco had a great knuckleball.

“It was filmed over 2010,” Dickey said. “It wasn’t always fun, but it was certainly very rich in the sense you have to think about some things you normally don’t think about. And they were right there. It was like a reality TV show. They had full access and I agreed to that. The knuckleball movie gives the audience not only a real sense of what the pitch is and how difficult it is to throw but also a good sense of the men who threw and throw it. I think that’s the real story line.

“You can’t make a 90 minute documentary about a ball that doesn’t spin unless you have a good story arc developed. They have that in Tim Wakefield’s quest for 200 wins. I’d say Wakefield and myself are the main characters, but there’s Phil Niekro, Charlie Hough, Tom Candiotti and Jim Bouton.”

Dickey keeps in touch with Hough. “I consider him a friend,” he said. “The brotherhood of knuckleballers is so small. We do something that only a few people that walk this earth have ever done. I don’t say that in a boastful way, just in a way that creates a very unique bond immediately. Charlie was the first guy I mentored under. When I had no idea what I was doing I went to Charlie. He invested in me in a way that was life changing. He gave me some things to be able to build off of to get where I am now.”

Which such an eclectic resume it’s interesting to think about the things Dickey could do after baseball.

“I don’t spend too much time thinking about that,” he said. “That’s only because I spent a lifetime not being in the moment—whether because it was too painful or because I didn’t have the equipment to live in the moment well. Now I try to fully invest in the moment. So I don’t think of five or ten years down the road as much as I think about how to live the next five minutes well because I know what I’m capable of if I don’t do that.

“When I do let myself go there, I think about being a full time writer. I don’t know how that will manifest. Maybe it’s another book, maybe a writer for a paper. Maybe I do both. But I do know this. When I walk away I have dragged my family to hell and back. To be a full time father and husband is something I want to do. I don’t know what I will do outside of that.”

I know this.

R.A. Dickey will continue to inspire.

Leave a Response