Burt Hooton & America’s Heartland

August 3, 2013—-

FORT WAYNE, IND.—-The highway flutters and spins out of downtown Chicago to rural central Indiana. You are looking for something, somewhere that tethers you to younger days. All the motels along Route 30 are sold out until you get to Warsaw, about 35 miles west of Fort Wayne. A ramshackle Super 8 has become an independent operation.

The night clerk is a heavy set woman sprawled out on a saggy sofa. She is watching a flickering television screen. With one hand she is playing a game on her laptop computer. It is her good hand. With the other hand she is swatting at flies with a green fly swatter. “You’re lucky,” she says. “Tomorrow we’ll be filled with migrant workers.”

You check in.

You are in the area to check out Burt Carlton Hooton.

Hooton, 63, is in his first year as pitching coach for the Fort Wayne TinCaps, the Class A Midwest League affiliate of the San Diego Padres.

You feel special ties to Hooton.

You were 16 years old sitting in the Wrigley Field left field bleachers on April 16, 1972 when Hooton no-hit the Philadelphia Philllies with his “knuckle curve” in his first start of season. You kept score despite the cold and light drizzle. Cigars cost anywhere between 15 cents and 30 cents and you know this because you saved the scorecard. It is a memory. It was a dark afternoon that drew only 9,000 fans, but there seemed to be clear sailing ahead.

Hooton was nicknamed “Happy” by Los Angeles Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda because he rarely smiled.

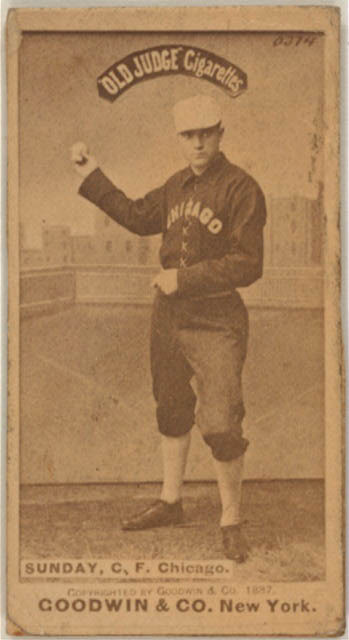

And, indeed, in a 30 minute conversation before a TinCaps game, the only time he smiles is when you mention your night in Warsaw. The funky motel is about a mile from the 1911 home of speedy Chicago White Stockings outfielder-turned evangelist Billy Sunday.

There is a new hipster restaurant in Logan Square called Billy Sunday, but this was the original (born 1862, died 1935).

Sunday lived in beautiful Winona Lake, which looks like a woody slice of Wisconsin in rural Indiana He built his home in 1911 on Mt. Hood, which overlooks the lake. The home is open for tours, but closed on Sunday.

Winona Lake is a wonderful destination with bike trails, boating and the Boathouse restaurant. The lakeside restaurant was built in 1895 as boat storage space for a religious summer resort.

According to the comprehensive 1992 Roger Bruns biography “Preacher (Billy Sunday and Big Time Evangelism),” the Winona Lake Year Book said the village centered around a Christian lifestyle “to shut out everything of doubtful tinge.” The village was linked to other cities through the Winona-Inter Urban Railway.

Bruns said the inside of the Sunday house featured photographs and paintings from Sunday revivals across America as well as a White Stockings team photo with only one clean shaven player.

Hooton has seen the highway marker for Sunday’s home from the bus tooling along Route 30.

What is he doing here?

“Started coaching in ‘88,” he deadpans. “Nine years with the Dodgers organization. Went to the University of Texas for three years. Went to the Astros, stayed 13 years with them. Was let go last year. Started looking for a job. And the Padres were the only ones who responded.” Hooton was the Astros pitching coach between 2000 and 2004.

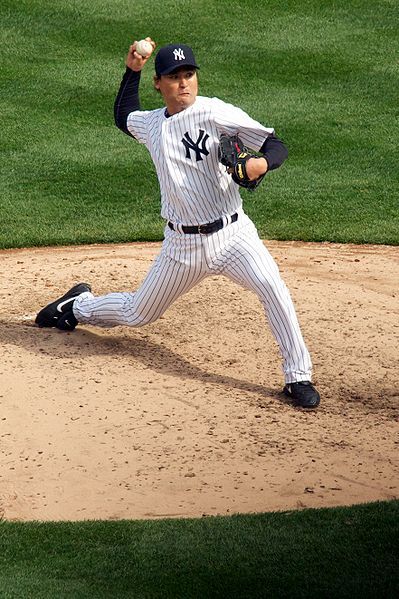

One of Hooton’s prize pupils is Chan Ho Park.

“When he first came to America he was 19, 20 years old,” Hooton says. “He spoke no English. He was the first South Korean to make it to the big leagues. They brought him to Los Angeles right away but that didn’t work out. So they sent him to San Antonio, where I was. I picked him up at the airport with him and his interpreter. It was so hard for him.”

Even Park’s Class AA games at San Antonio were broadcast back to South Korea. Hooton taught Park how to pitch and not to always rely on his high fastball. Hooton also told Park he needed to learn English.

“I remember him coming to me one day crying,” Hooton says. “He felt his teammates didn’t like him because they were kidding around with him. I said, ‘Chan Ho, that means they do like you. When they don’t like you they won’t do anything with you’.”

Park ended up pitching 17 years in the major leagues and his 124 wins are the most ever by an Asian pitcher. Hooton and Park, now 40, still keep in touch. “He will call me on Father’s Day,” Hooton says. “He will call me on Christmas. He has a house in Korea, a house in L.A. a house in Dallas and a house in Las Vegas he is trying to get rid of.”

And Hooton was in on the ground floor.

Hooton is deploying the six-man pitching rotation at Fort Wayne. Padres farm director Randy Smith believes that two bullpen sessions help younger pitchers build muscle memory that better allows them to repeat their deliveries. The six-man rotation came into play late last year at Fort Wayne and high class A Lake Elsinore.

“Most of the pitchers are in their first full season of professional baseball, they come right out of high school or college and they’re not used to playing 140 game schedule,” he says. “They’re not used to pitching every five days, so to speak. The idea is to slowly indoctrinate them into full season professional baseball. It cuts down on their innings. We monitor the number of pitches they throw in each start (under 95) and in between starts. As they mature and grow, they will go back into a five man rotation in a higher league.”

“They (his pitchers) didn’t start any younger than I started,” says Hooton, who broke in with the Cubs at age 21. “It’s just a different philosophy now. There’s much more money invested in the players now so you’re protecting your investment.”

Hooton was the Cubs second pick in the 1971 amateur draft out of the University of Texas where he was a three-time All-American.

He made his first major league start nine days later. He struck out the first batter he faced—Lou Brock.

At the time, Hooton was only the third player to go straight to the major leagues without playing in the minors. “After my first start I developed tendonitis in my shoulder and pretty much sat for the rest of June,” he says. “They wanted to get me pitching on a regular basis so they sent me to Tacoma. I did quite well (he led the Pacific Coast League with a 1.68 ERA), came back to Chicago in September and stayed in the big leagues for the rest of my career.”

His no-hitter came in his fourth major league start.

“It was a cold day,” he recalls. “The wind was blowing in, which was a good thing. A couple balls were hit that might have gone out otherwise. It was right after a 13 day strike, I’m sure no one was sharp. I wasn’t sharp. I walked seven guys (and struck out seven).”

Hooton was self-taught on his knuckle curve, which he began throwing at age 14.

The pitch is thrown like a curve ball, but flutters like a knuckleball.

“I logically assumed you put your knuckles down on the seams of the ball to throw a knuckleball,” he explains while reaching for a baseball. “I heard them say to push it out. Every time I pushed it out I got rotation. I never could throw a regular knuckleball. First, I held it wrong. You hold that with your fingertips. So when I pushed it out, I threw it hard and it became a curve ball. From 14 on up it became my curve ball.”

Hooton said some young pitchers ask him to show them the pitch, but no one searches out Hooton like R.A. Dickey found a mentor in Charlie Hough. “Nowadays kids are looking for a quick fix more than anything else,” he says. “We live in a take-a-pill society where one pill cures everything.”

Hooton does not smile.

“We did not have a lot of pitching coaching when I started,” he says. “Actually I’m not real fond of the pitching coaching that I got. Fred Martin was the so-called (Cubs) pitching coordinator. Two months in the minor leagues, I didn’t spend a lot of time with him. I was one of those guys who had been better off if they left me alone.

“When I got to Chicago and did what I did in Tacoma—pitched 102 innings and struck out 135—, pitched the no hitter to start the season in ‘72—in three and a half years with the Cubs I had four different pitching coaches. They were all sinker, slider guys. I was a four seam fast ball, four seam curve ball. They started telling me I needed to throw sinkers and sliders. Well, three and a half years later I couldn’t get anybody out.”

In May, 1975 Hooton was traded to the Dodgers for the forgettable Eddie Solomon and Geoff Zahn. Hooton was acquired to replace Tommy John, who was on the shelf with now historic elbow surgery.

“The pitching coach in Los Angeles was Red Adams, who was the best pitching coach I ever had,” Hooton says. “He told me to can the sinker and slider and pitch the way I wanted to. As soon as he told me that I won 18 games. That’s how coaches can hurt guys.

“I live by Red’s philosophy. The two things he taught me is that you can’t coach anybody who doesn’t want to be coached and the worst thing a kid can come up against is a coach who thinks he has to coach. You look and see what kids do well and try to build on that rather than telling them what to do. I’m not that smart.”

Look for two of my baseball stories in the upcoming anthology “From Black Sox to Three Peats (A Century of Chicago’s Best Sports Writing From The Tribune, Sun-Times & Other Newspapers), edited by Ron Rapoport on University of Chicago Press.

Leave a Response