Remembering a Beloved Birmingham bat from the Negro Leagues

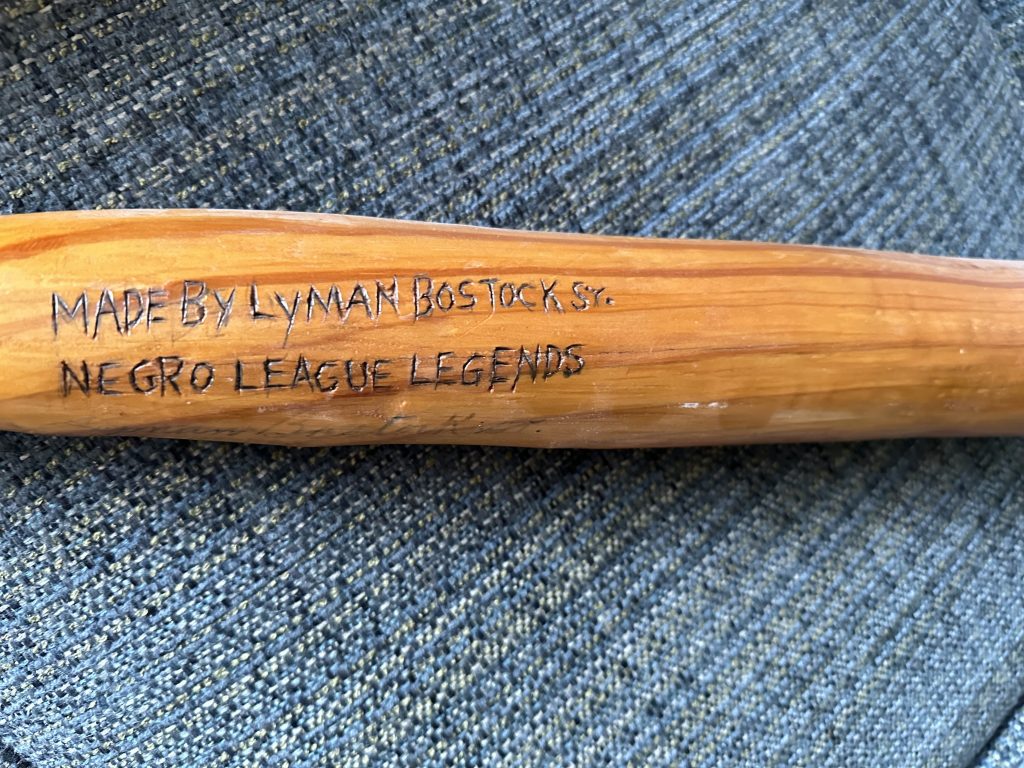

A hand-carved baseball bat sits atop a bookshelf in my office. It was made by the Birmingham Black Barons first baseman Lyman Bostock, Sr. The bat is beautifully finished and lacquered. Bostock’s name is wood burned into the bat with the title “Negro League Legends.” The bat is 36 inches long but it covers miles of distinguished memories.

It is a magic wand.

I purchased the folk art from Bostock in 1994 when the Chicago Sun-Times sent me to Birmingham, AL. to trail Michael Jordan playing minor league baseball for a few days. I was privileged to have many meaningful assignments at the newspaper. This remains near the top of the list. Meeting Bostock was more memorable than watching Jordan.

I had written about the Negro Leagues at the Sun-Times and I knew about Rickwood Field (capacity 10,800) in Birmingham, which is the site of this year’s “Field of Dreams” type game on June 20 between the San Francisco Giants and St. Louis Cardinals.

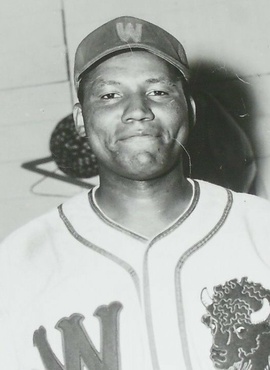

In 1994 I went off the media grid that was following Jordan around. I figured out how to connect with Bostock who was 76 years old. His son was the Minnesota Twins-California Angels outfielder Lyman Bostock, Jr. who on Sept. 24 1978 was murdered in a vehicle in Gary, IN. when he was visiting relatives after the Angels played the White Sox. Bostock, Jr. was 27 years old.

The fine Sun-Times photographer Phil Velasquez and I went to pick up the Negro League Legend at his house in my small rental car. Bostock was a big man, probably in the neighborhood of 235 pounds. He only lived a few miles from Rickwood. He played for the Black Barons between 1940 and 1946. He died on June 24, 2005.

Lyman Bostock, Sr.

Bostock told us he had not visited Rickwood since he played baseball. Rickwood had fallen on hard times. It was in a grassy run-down state and was only used for high school games.

Construction on Rickwood was completed in August 1910, just ten days after Comiskey Park was dedicated. At the time the iron-and-steel city of Birmingham was the fastest growing town in America. Rickwood got its name from Barons’ owner A.H. “Rick” Woodward, who owned a Birmingham iron company. He was fishing buddies with Ty Cobb and Woodward recruited Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics to lay out the field.

Rickwood was modeled after Forbes Field in the steel enclave of Pittsburgh, Pa. Babe Ruth, “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, Ty Cobb, Hank Aaron, and Willie Mays all played at Rickwood. The ballpark has a hand-operated scoreboard like Wrigley Field and Fenway Park.

The Class AA Birmingham Barons left Rickwood in 1987 for a new stadium in suburban Hoover and that’s where Jordan played. The White Sox Jack McDowell started the last professional game at Rickwood in September 1987. The Barons lost to Charlotte 5-4 in the second game of the Southern League Championship Series. There were only 2,392 people in the stands.

As we left his house Bostock put on his black BBB (Birmingham Black Barons) baseball cap. He squinted into the distant sun and tilted the beak of the cap over his forehead to add even more dignity to this road trip. The Birmingham native was delighted to be going back to a place where he once was so young and free. Memories flowed like water down a winding river.

Bostock recalled watching games from nearby trees as a 12-year-old. He remembered a lumber yard in an empty lot over the right field fence. He said he got a base hit off of future Hall of Famer Satchel Paige the first time he saw him–at Rickwood. “He threw what we called aspirin tablets,” Bostock told me. “He could throw the ball wherever he wanted. Underhanded. Sidearm. Overhand. All the same pitch.” And in a twist of serendipity, the former Pittsburgh Pirate pitcher Bob Veale was the stadium groundskeeper, and was cultivating the pitcher’s mound. The 6’6” Veale was 58 years old. Another Birmingham native, Veale had been working at Rickwood since the age of seven. His father was a pitcher for the Negro League’s Homestead Grays.

Rickwood Field, Birmingham, AL

The Birmingham Black Barons were charter members of the Negro Southern League in 1920. They started playing at Rickwood in 1924, alternating weekends with the White Barons. A young Veale worked the concession stands.

Besides stints with the Black Barons in 1940-42 and 1946, Bostock played with the Chicago American Giants (1947 and 1949) and the New York Cubans (1948). Seamheads.com has Bostock hitting .466 during his 1941 season for the Black Barons, higher than Ted Williams’ .406 for Boston in 1941. MLB did not recognize Bostock because he only had 84 plate appearances. Years of diligent research of verified box scores and newspapers have uncovered missing Negro League games. Sean Forman, president of Sports Reference recently told the New York Times that they have recorded 23 games of 1941 records for Bostock but the Black Barons played 45 games that season. Bostock also played in the 1941 East-West All-Star Game before 50, 246 fans at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Bostock is still carving out his name in the game.

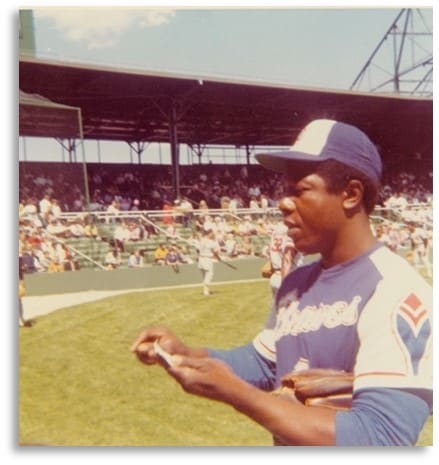

Atlanta Braves era Hank Aaron at Rickwood

Bostock told me it took him 35 hours to hand-carve and finish a Formosa, oak, or pine baseball bat. He did not have a home workshop. He made the bats on his patio. Even at age 76, he was making furniture for his family, African sculptures he called Body & Soul and Moon Man, and the bats which he numbered between 45 and 50. He began woodworking in the 1950s after playing baseball for the Winnipeg Buffaloes in Canada’s ManDak League. He noticed how natives made dishes out of Formosa trees. When Bostock returned to Birmingham he deployed the trees from the side of his mother’s house for his artwork.

The updating of Negro League statistics and the June 20 MLB tribute to the Negro Leagues only begins to give these players proper recognition. After the White Sox left the original Comiskey Park in 1990, Rickwood became the oldest functioning professional baseball stadium in America. In 1993 Rickwood was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. A few weeks before our 1994 visit, scenes from the Tommy Lee Jones movie “Cobb” were filmed at Rickwood where the late singer-songwriter-Cubs fan Jimmy Buffett had a bit role as a heckler. According to the Friends of Rickwood, of the 351 members elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, 181 played, managed or umpired at Rickwood.

Neither Bob Veale nor Lyman Bostock, Sr. are in the Hall of Fame, but on that singular sun-kissed afternoon in the summer of 1994, they stood for something bigger. They were home and they were proud.

Their conviction and passion are only beginning to make baseball the connective thread that was denied for many years. The Bostock bat in my office is nice to look at, but I think more about the old hands that made it so beautiful. They are wrapped around my heart and mind.

PROGRAMMING NOTE:

My friend Michael Marsh is conducting a Zoom presentation about the late Chicago journalist and civil rights pathfinder Wendell Smith for the Josh Gibson Foundation at 11 a.m. CST this Saturday, June 15.

Michael is a former staff writer for the Chicago Reader, he has also covered high school sports for the Sun-Times and Chicago Tribune. He wrote the biographical introduction for The Wendell Smith Reader, a magnificent compilation that was published by McFarland in 2023.

People can register for “Pittsburgh and the Rise of Wendell Smith” through the following link: https://us02web.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_m6_sxscmTtaoYI9_FoHjNg.

Leave a Response