Gene Barge: The Sound of a Dream (1926-2025)

In these times it is important to know the strength of one voice: a clarion of dignity, grace, and conviction. When delivered on note it becomes a sound that can move others forward.

In these times it is important to know the strength of one voice: a clarion of dignity, grace, and conviction. When delivered on note it becomes a sound that can move others forward.

That was the sound of Chicago musician Gene Barge.

Barge died Sunday of natural causes at his home in the Bronzeville neighborhood of Chicago. He was 98 years old.

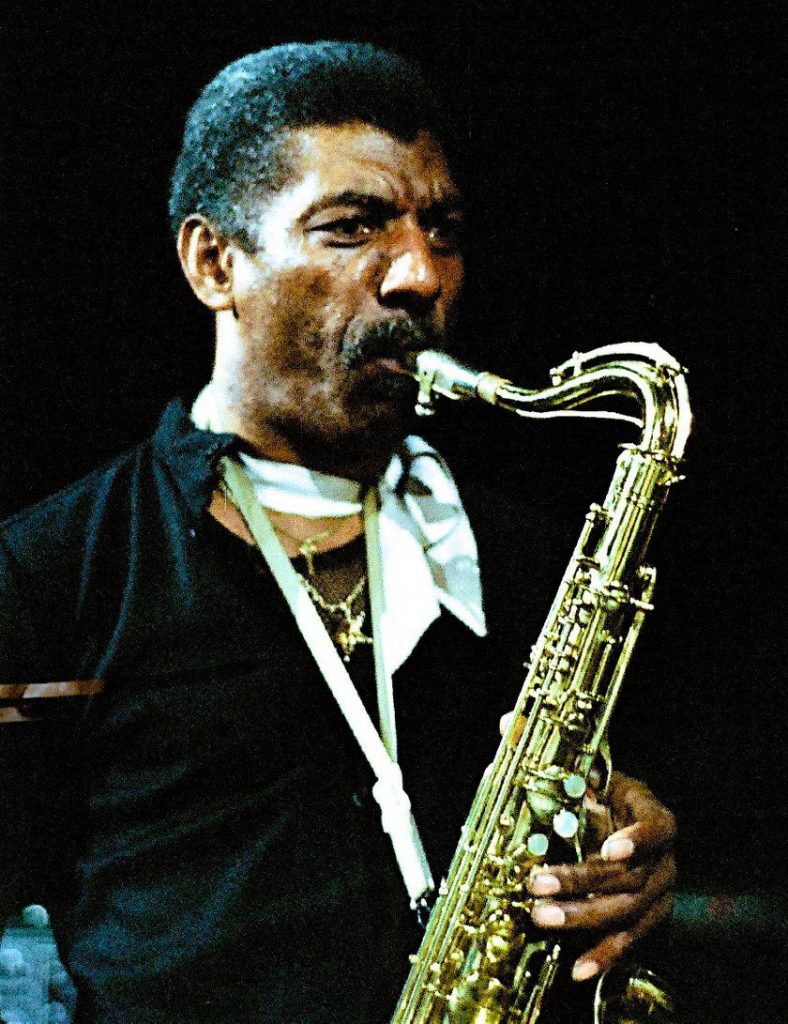

He achieved national fame in 1961 with the Gary U.S. Bonds hit “Quarter to Three,” on which he produced and played saxophone. Bonds sang how “I danced ‘til a quarter to three, with the help last night of Daddy G.” That was Barge’s nickname.

Barge was arranger, producer, and sax player at Chess Records, 2120 S. Michigan, from 1964 until 1967 when Chess moved to a bigger space at 320 E. 21st St. Barge continued with Chess, shaping Little Milton’s “Grits Ain’t Groceries” album as one of the first hits out of the new space. Chicago film director Andrew Davis cast Barge as the band manager in 1978’s “Stony Island” and 1993’s “The Fugitive” where Barge played a Chicago cop.

For me, Barge’s most important contributions were at the grassroots in his adopted hometown of Chicago.

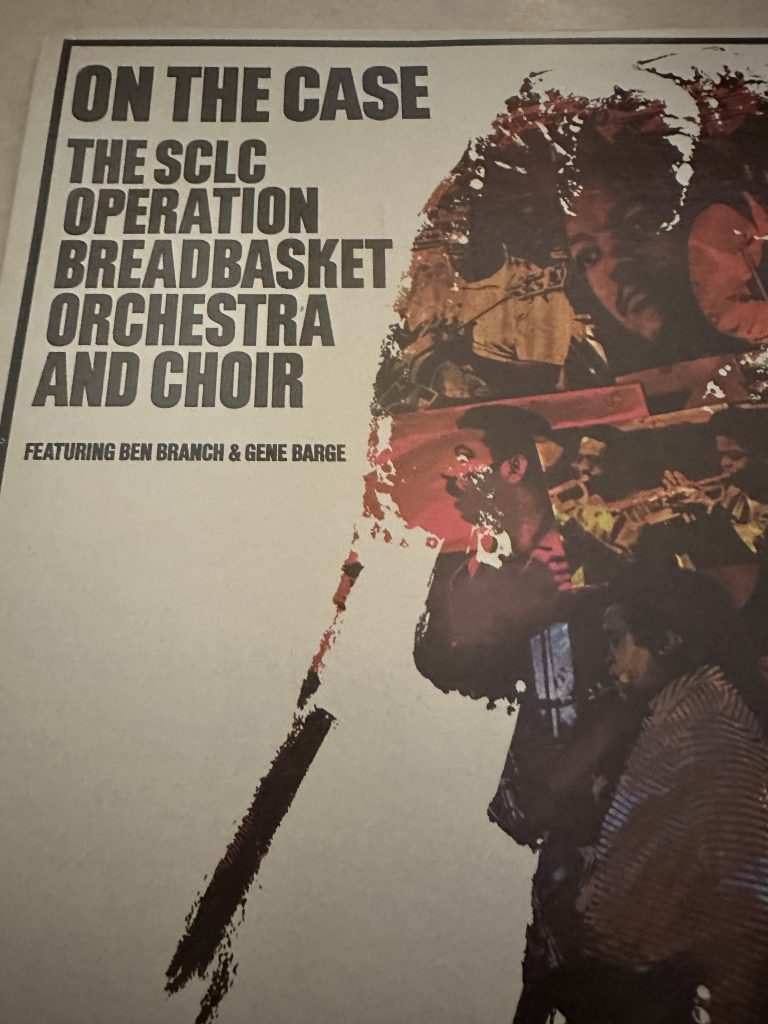

He was the leader of the late-1960s Operation Breadbasket Band, an arm of the SCLC (Southern Christian Leadership Conference). The Chicago post of Operation Breadbasket was founded in 1966 by Rev. Jesse Jackson to empower Black-owned businesses.

Breadbasket band members included saxophonist Ben Branch, who was with Dr. Martin Luther King when he was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Count Basie trumpet player Maury Watson, and the great Bobby “Blue” Bland guitarist Wayne Bennett.

Barge produced the gospel-soul “On The Case: The SCLC Operations Breadbasket Orchestra and Choir” for Chess. The album includes Barge’s evocative tenor sax on “What a Friend We Have in Jesus” and Barge leading the 21-piece orchestra and 200-voice choir in “We Shall Overcome” and the 1900 hymn “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” known as The Black National Anthem.

In a 2013 interview The Rev Jackson told me that “Dr. King was looking for something meaningful to inform people. And people came from miles around to hear the band. That band set the tone for a dynamic in gospel music, bringing in a big band sound. You had top-notch studio musicians and they were awesome.

“But none of them quite had the sound as sweet as Gene Barge. Gene is a phenomenal and serious saxophone player. How can you explain tonality? You know when Gene is in the house.”

Gene Barge made Chicago a better place to live.

Barge was always there for me to answer my questions about Chicago’s cultural history. I invited him to the Chess Records studio a few times, including a live taping we did for WGN-AM. He would recall exactly where Maurice White (who would go on to form Earth, Wind, and Fire) would set up in the drum booth. I took him to screen the 2008 film “Cadillac Records” sort of about Chess Records. He was not impressed with Beyonce’s take on Etta James.

And in 2013 he invited me and photographer Paul Natkin to “The Round Table,” a group of socially conscious Chicagoans who met regularly at the city’s soul food restaurants. I was researching our 2015 book “The People’s Place (Soul Food Restaurants and Reminiscences From The Civil Rights Era to Today)” [Chicago Review Press]” Barge was the unofficial leader of the group.

Gene Barge (L) and Rudolph Brown at The Round Table (Paul Natkin photo).

Barge was born in Norfolk, Va. and attended West Virginia State College where he majored in architecture. He later became an English and Social Studies teacher at Suffolk High School in Virginia. His first major exposure was playing the sax solo on Chuck Willis’s 1957 hit “C.C. Rider.” He migrated to Chicago in 1964.

“When I got to Chicago from Norfolk it was turbulent,” Barge said in the 2013 Round Table meeting at Pearl’s Place, 39th and Michigan. “Dr. King had been in Chicago in 1963 and ‘64 and declared Chicago as one of the most racist cities in America. Boston. Chicago: segregated. Supposed to be free, but segregated. In the south we had white folks across the street. We were segregated, not by sections of town (as in the north), but by the system.

“There was a revolution in society. When I started with the group (Round Table) in ‘64, most of the guys belonged to the SCLC , various community groups. Some guys were dealing with housing over on the south east side. ” Round Table members then included Ben Branch, Bennett, and Chuck Bowen, an administrative aide to Mayor Richard M. Daley.

Barge said The Round Table was at its peak in the late 1960s and 70s at Sauer’s, 321 E. 23rd St. Sauer’s, ironically, was a building constructed in 1883 to hold a dancing academy for Chicago’s upper crust, including Marshall Field. Sauer’s had considerable cultural weight because it was next door to Paul Serrano’s recording studio. The jazz trumpet player-engineer recorded politically charged artists like Jerry Butler, Donnie Hathaway and Oscar Brown, Jr. on East 23rd St.

Jazz was one of Barge’s first loves. He didn’t like the fact that “Cadillac Records” skated over the Chess Records jazz roots. Leonard Chess arrived on the local music scene in 1949 by opening the groovy Macomba Lounge, 3905 S. Cottage Grove. The late-night club attracted jazz artists like Ella Fitzgerald and Dinah Washington, who were headlining earlier in the evening at other Bronzeville venues.

“(Jazz pianist) Ahmad Jamal was one of the greatest artists at Chess,” Barge told me in 2008. “Ramsey Lewis did more than 20 records for Chess (on the label’s Argo and Cadet imprint.) One of the first people the Chess brothers recorded was (Chicago tenor saxophonist) Gene Ammons. Jazz guys coming to jam at the Macomba is what got the whole thing going.”

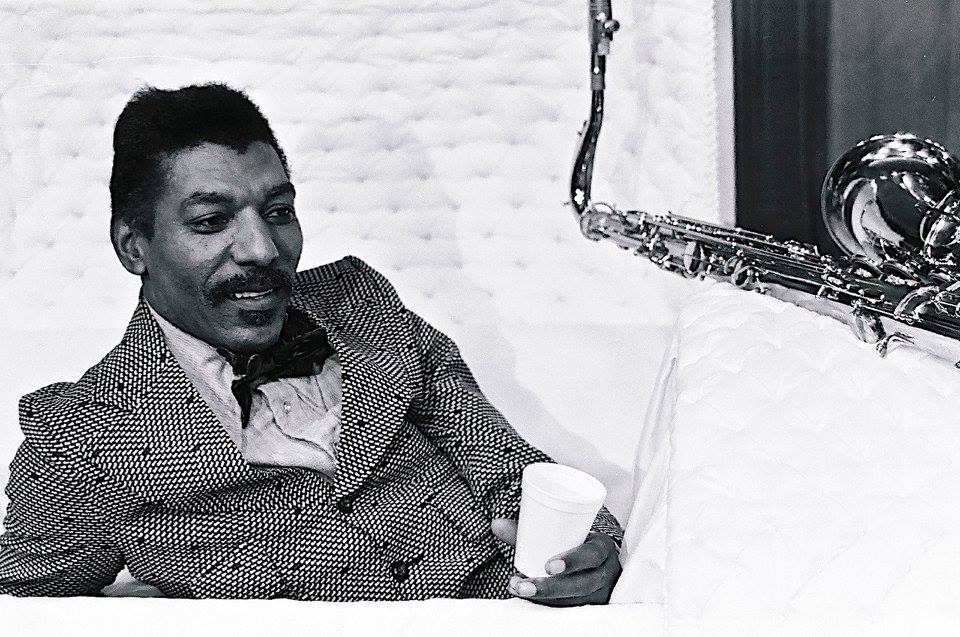

In a Christmas-time 2013 conversation Barge called Chicago the most diverse city in the world–musically. “The acclaimed (CSO) symphony with Dale Clevenger,” he said. “There’s no other city that has produced the blues luminaries Chicago has produced. And let’s go to jazz. Two or three of the greatest tenor players came from here: Johnny Griffin, who was one of my idols although one of my heroes is Gene Ammons, whom I patterned my style after. It was a feeling. Most jazz saxophone players try to be impressive, play a lot of notes and complex ideas. Gene Ammons always played melodic and invented soulful passages. He had one of the biggest tones in the business.

“We need to go back and listen.”

Buddy Guy and Gene Barge (R), photo from Gene’s FB page

Barge would use his teacher’s soul to go on to make a major imprint on contemporary music. While at Chess he worked with Muddy Waters, Buddy Guy, the fantastic soul singer Billy Stewart, Fontella Bass and many others. Towards the end of Willie Dixon’s life in the late 1980s, Barge helped the Chess songwriter-bassist copyright some of his songs.

Barge left Chess in 1973 to head the gospel music division at Stax Records in Memphis. After Stax, Barge worked with Natalie Cole and won a Grammy for co-producing her 1976 hit single “Sophisticated Lady.” He toured with the Rolling Stones in 1982 and then became a member of the popular Chicago R&B review Big Twist & the Mellow Fellows which morphed into the popular Chicago Rhythm and Blues Kings.

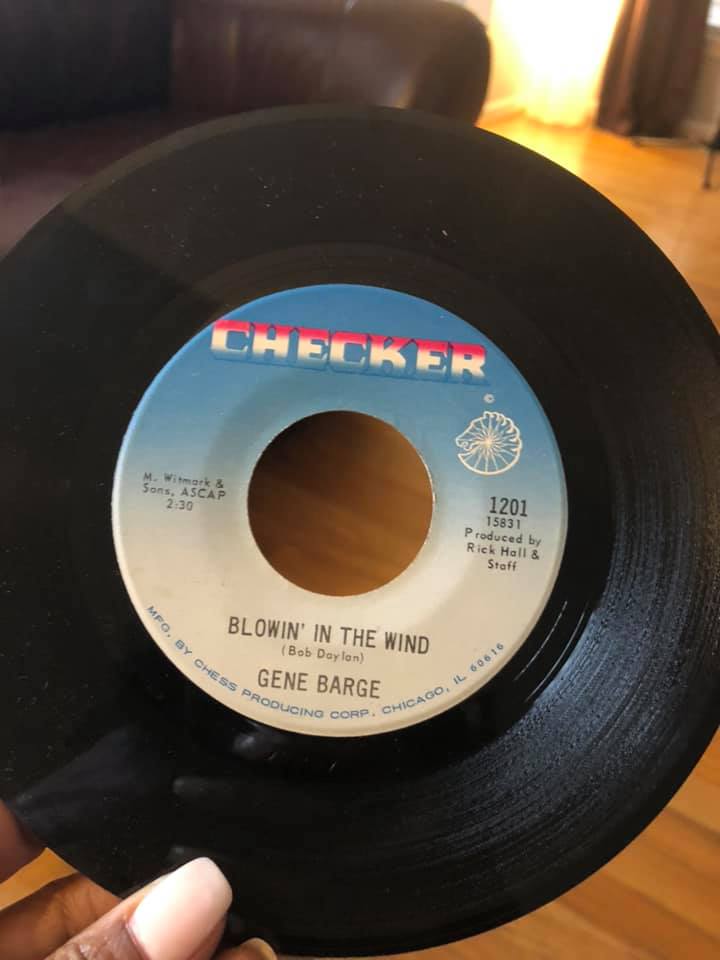

One of Barge’s most outside-the-box efforts was the 1968 Checker single “Chippie The Hippie From Mississippi” Barge wrote the tune with his late pal Charles Stepney (Earth, Wind and Fire, Rotary Connection) and took over vocals. The flip side was an instrumental version of Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind,” produced by Rick Hall of Muscle Shoals fame.

Barge was a cornerstone of “The Norfolk Sound” that influenced Bruce Springsteen and Southside Johnny Lyon. In January 2012 I flew to Norfolk for a tribute to saxophonist Clarence Clemons who was born and raised in Norfolk County. Johnny Lyon drove eight hours from New Jersey just to be there.

The concert was heled at the precious Attucks Theatre, (est. 1919) the oldest African-American-operated theater in America. “Norfolk was one of the big ports with a lot of Black sailors,” Lyon explained after record shopping. “Gary Bonds was part of it. Gene Barge was part of it. There was that sense of beat, but a real swampy atmosphere. There was so much echo and you could hear people in the background. We responded to that in New Jersey. There’s an ambiance that comes from that.”

The thread in Gene Barge’s diverse resume was his faithful pursuit of justice and equality. Every time I was around him he carried himself with dignity. He always educated me. We once talked about the legendary Hotel Theresa, a.k.a. “the Waldorf of Harlem” in New York. In 1959 Malcom X enjoyed dinner with Fidel Castro at the Hotel Theresa. “During the movement civil rights ideas were hatched at the lunch counter of the Theresa,” Barge said. “Blacks couldn’t go downtown. And that’s New York. But they were selling soul food, even though Castro was cooking chickens in his room.”

And Barge would champion the rich legacy of Chicago music every time he was near Chess. “This is a historic street,” he said during one visit to the 2120 S. Michigan landmark. “During lunch break, you’d go downstairs and you could see anybody standing outside. Muddy. I remember (jazz saxophonist) Sonny Stitt out there talking. (Saxophonist) Roland Kirk. Ahmad Jamal. Etta James and Sugar Pie (De Santo) would run out to get some food. They’d bring back cheese and crackers and sit in the middle of the floor eating them, talking that talk. One day Ike and Tina Turner pulled up in this big Chrysler. They were trying to get a deal. I guess we took it for granted.”

It is sad to know this generation of essential American history is moving on. But I also know that Gene Barge’s sense of empathy will remain in our music, our neighborhoods and in our hearts.

Do not take that for granted.

Dave , Is there anyway please you could sent me a link to After The Glitter Rain please. This is a MUST READ for me. Would be very appreciative and grateful. THANK YOU Steve

https://newcityshop.com/collections/newcity-magazine-current-issue/products/april-2025-issue-the-big-art-issue-print-edition